Despite a Botched Execution and Concerns Over Innocence, Oklahoma Prepares to Execute Julius Jones

Persistent problems with lethal injection have not swayed the state’s determination to put Jones and five other men to death. Liliana Segura November 14 2021, 6:30 a.m.

On the day of Julius Jones’s clemency hearing, a crowd began gathering well before 8 a.m. at the Tabernacle Baptist Church on Oklahoma City’s northeast side. They were dressed for warmth, in winter hats, hoodies, and face masks that read “Justice for Julius.” Some, such as Abraham Bonowitz of

Death Penalty Action, were veteran anti-death penalty organizers. Others, like Eugene Smith, were new to the cause. Standing in the parking lot, Smith propped up a massive green banner featuring Jones’s face. It read “Are YOU Willing to Be the Innocent Person Executed?”

“We’re here to free an innocent man on death row,” Smith told me, adding that he wanted to raise awareness about other cases too. A few days earlier, on October 28, Oklahoma had carried out its first execution since 2015,

killing a 60-year-old Black man named John Grant by lethal injection. Like the previous two men sent into the state’s death chamber — whose botched executions

thrust Oklahoma’s dysfunctional capital punishment system into the national spotlight — Grant struggled before he died. Witnesses described how he vomited and repeatedly convulsed shortly after the lethal injection began. Yet officials denied that anything had gone wrong.

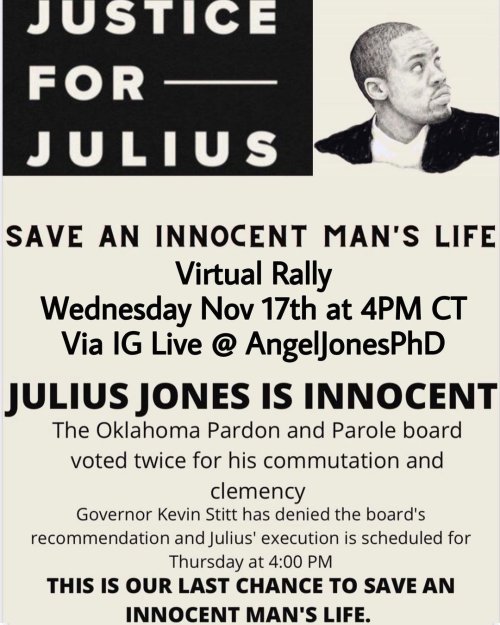

Now Jones faces the danger of a similar fate. Despite pending federal litigation over the state’s execution protocols — and a recommendation from the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board that Jones’s sentence be commuted to life in prison — Jones is scheduled to die on November 18 for a crime he swears he did not commit.

Jones was sentenced to death in 2002 for killing a white man named Paul Howell in an affluent suburb of Oklahoma City. The case rested largely on a single eyewitness account, along with the testimony of two confidential informants. Although the alleged murder weapon was recovered from his parents’ home, Jones insists that he was framed by his co-defendant, a former high school classmate named Christopher Jordan, who testified against him in exchange for a secret plea deal. Jordan was released after 15 years in prison.

Jones’s case was relatively obscure outside Oklahoma until 2018, when ABC aired a seven-part documentary series titled “The Last Defense.” Produced by actor Viola Davis, it laid out the case for Jones’s innocence — and catapulted his name into the public eye. Recent

opinion polls taken from Oklahoma voters showed that 60 percent of those familiar with Jones believed that his death sentence should be commuted. Yet the publicity around his case has also sparked backlash from prosecutors and Howell’s family, who accuse Jones’s supporters of manipulating the public by misrepresenting the facts. After years of refusing interview requests, the family

told a local TV station in September that they felt re-victimized by the celebrity-studded movement in support of Jones. “This is David versus Goliath,” Howell’s nephew said.

Around 8:15 a.m. on November 1, Rev. Cece Jones-Davis took the mic in the church parking lot. A minister and social justice activist, she had helped lead countless actions in Oklahoma City in the days before the clemency hearing. “What makes this different,” Jones-Davis told the crowd, “is that today Julius Jones gets to speak for himself.” After a prayer, the crowd turned out of the parking lot toward Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue. Chanting and waving signs, they passed the headquarters of Oklahoma’s Department of Corrections, then arrived at another church.

Cars parked outside had “Justice 4 Julius” written on the windows. A spread of fruit, granola bars, and honey buns was laid out under a blue tent. Rows of folding chairs were arranged to face a women’s prison across the street, the location where the hearing would take place. A large set of speakers sat ready to broadcast the proceedings. “Julius Jones is innocent!” a man shouted f

Left/Top: Oklahoma City activist Adriana Laws leads a march in support of Julius Jones on the morning of his clemency hearing. Right/Bottom: Demonstrators listen to the clemency hearing as it is broadcast across the street on Nov. 1, 2021.Photos: Liliana Segura/The Intercept

The Zeal to Kill Among the country’s dwindling death penalty states, Oklahoma leads the nation in executions per capita. Although the state reflects national trends in residents’ waning support for capital punishment — and in the declining number of death sentences imposed year after year — Oklahoma remains a bastion in its willingness to carry out executions. “If you look at the states that are outliers in their zeal to kill, they are also the states that are outliers in their failure to provide fair process,” said Robert Dunham, executive director of the

Death Penalty Information Center.

“Oklahoma has had six years to think about how not to botch an execution, and they squandered it.”

Apart from Jones, five more men are set to die in Oklahoma between December and March 2022. Lawyers for those men are fighting largely under the radar to save the lives of their clients, whose cases reveal longstanding flaws with the death penalty, from ineffective lawyering to prosecutorial misconduct. According to Assistant Federal Public Defender Emma Rolls, head of the capital habeas unit of the Western District of Oklahoma, these cases also reflect “systemic failures resulting in generations of unbelievable poverty, childhood deprivation, mental illness, addiction, and trauma.”

Perhaps more disturbing is Oklahoma’s determination to kill the men despite persistent problems with its execution protocols — problems officials claim to have worked diligently to fix. “Oklahoma has had six years to think about how not to botch an execution, and they squandered it,” said Dunham. In its rush to kill Jones, Oklahoma appears not only unbothered by its ugly death penalty history but also intent on repeating it.

In September 2015, Richard Glossip came

within moments of being killed at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester when the execution was abruptly called off. Glossip swore he was innocent — and an

investigation by The Intercept had found his conviction to be disturbingly flimsy, based almost solely on the account of a 19-year-old co-worker who admitted to killing the victim but blamed Glossip for coercing him. Yet Glossip’s execution wasn’t stopped due to the lingering questions about his guilt. Instead, prison officials explained that they had received the wrong drugs from their supplier, discovering the mistake at the last minute.