Original Articled titled: The Black immigrant who challenged US segregation – nearly 190 years ago” [ Because of my distaste for labeling Human Beings as colours (white/black); I have changed some parts of the article ]

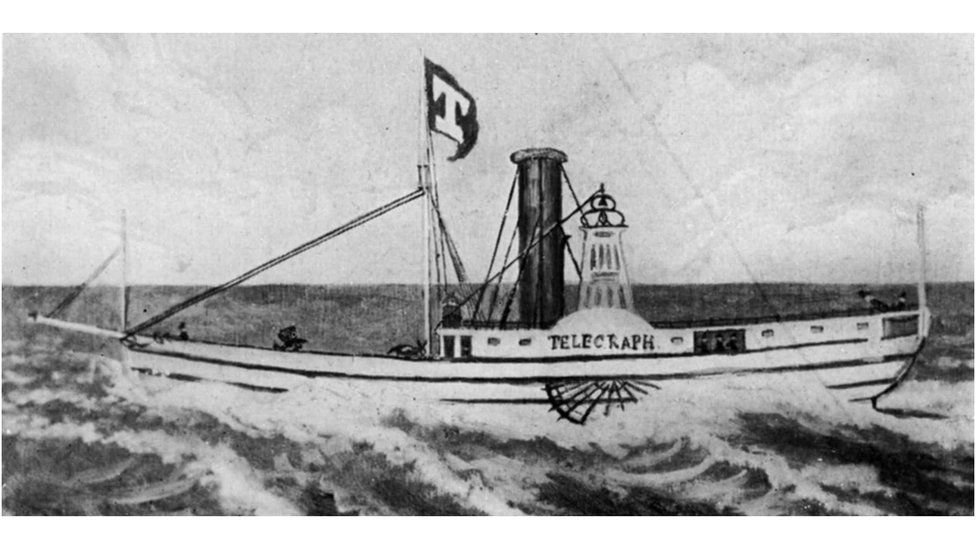

In 1832, the Mundrucu family refused to be barred from an area exclusively for Caucasians on the steamboat Telegraph

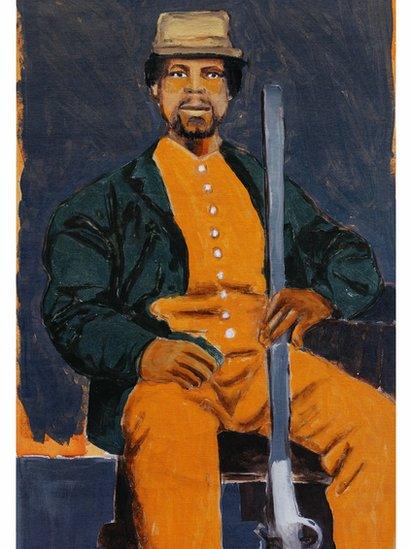

It was a cold, rainy day in November 1832 when Brazilian immigrant Emiliano Mundrucu boarded a steamboat – the Telegraph – with his wife Harriet and their one-year-old daughter Emiliana.

They were taking a business trip from the Massachusetts coast to Nantucket Island, in the northeast of the United States.

During the crossing, Harriett, who wasn’t feeling well, tried to seek shelter with her daughter in an area of the ship exclusively for women, but their path was blocked.

The reason?

They were of African descent, and only Caucasian women were allowed in the ladies’ cabin, comfortable accommodation with private berths.

At that time, slavery was no longer allowed in northern states (it persisted until the Civil War in the US south), but segregationist practices separating Caucasians from “coloured” people were growing.

However, the Mundrucu family did not accept their exclusion and the episode led to a pioneering lawsuit against racial segregation in the United States – proceedings that were big news at the time, but were later forgotten and have only recently been rediscovered by historians.

The case went to court after Harriett insisted on entering the ladies’ cabin with her child, while the captain of the boat, Edward Barker, argued with Mundrucu – a Brazilian revolutionary who fled to Boston after being sentenced to death for his role in an attempt to create a republic in northeastern Brazil in 1824.

“Your wife a’n’t a lady. She is a n—er,” Barker told Mundrucu.